Ecuador’s embassy in the United States had never sought the spotlight.

Set back one block from the former Spanish and Mexican embassies, and current Polish, Lithuanian and Cuban embassies, the Beaux-Arts building with a cracked chimney and a fire-scarred roof at 15th & Euclid seems tucked away like a secret. The four-story mansion was designed by architect George Oakley Totten Jr.,whose work shaped much of early diplomatic Washington. Commissioned during Mary Foote Henderson’s quixotic campaign to create a second Embassy Row along Meridian Hill, the building reflects Totten’s signature blend of Parisian formalism and local restraint: a limestone base, arched windows, a steep mansard roof, and symmetry that conveys authority without grandeur.

For most of its life, the building at 2535 15th Street NW served its purpose with quiet precision: visas, trade meetings, small receptions that began at six and ended at eight. But that all changed on a humid afternoon in 2019, when, with little fanfare, the government of Ecuador allowed British police to enter its London embassy and arrest WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. The moment was decades in the making and the implications landed squarely in Washington, D.C., where the embassy became a front-row seat to the diplomatic fallout—a test of how much strain a century-old partnership could take.

Ecuador and the United States formalized diplomatic relations on June 8, 1848, less than two decades after Ecuador broke from the short-lived Republic of Gran Colombia. Washington dispatched its first chargé d’affaires, John Trumbull Van Alen, to Quito that year, marking the beginning of a bilateral relationship shaped less by ideology than by geography, trade, and strategic proximity.

In the early years, Ecuador’s diplomatic mission operated from various locations, reflecting the evolving nature of international relations and the growth of diplomatic infrastructure in the U.S. capital. For example, a photo from the early 1920s puts the Ecuadorian delegation at 1633 16th Street. In 1955, the embassy also became the refuge of the White House Spanish-Portuguese Study Group, which had been “organized in 1943 for the purpose of strengthening relations between this country and the people of Latin America,” according to The Washington Post. Why the group, which had been created as a joint effort between First Ladies Truman and Eisenhower, had needed to seek an alternative location while Mrs. Eisenhower was still in the White House, remains unclear. But the Ecuadorian Embassy welcomed the group with an afternoon tea.

Shortly after, the Ecuadorians themselves began looking for an alternative location. By this point, the mansion at 2535 15th Street had served several purposes, at one point housing the Ghanaian Embassy. In the 1960s, the Embassy of Ecuador purchased it, and established their formal, permanent embassy in Washington.

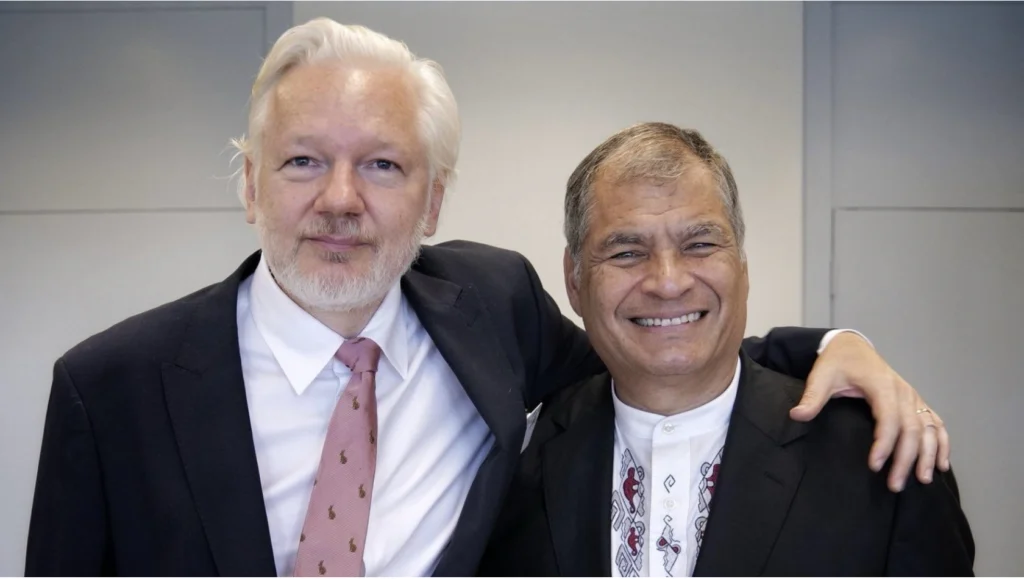

In 2010, controversial whistleblower Julian Assange leaked confidential American government documents relating to U.S. operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. In order to prevent possible extradition to the United States for these actions, Assange appealed for political asylum at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. When President Rafael Correa granted the appeal, Ecuador inserted itself directly into a storm it had not created but would be forced to weather. The London embassy took the heat, but it was in Washington where Ecuadorian diplomats felt the long-term effects.

Suddenly, the D.C. embassy was fielding calls, dodging questions, and holding uncomfortable meetings. The move was framed in Quito as a defense of free expression and sovereignty. In Washington, it was read as antagonism.

Correa’s broader foreign policy—aligned with Venezuela and Bolivia, critical of U.S. drug policy and military presence—made compromise difficult. The embassy found itself in a defensive crouch, operating more as a firewall than a bridge.

Inside, work continued—visas issued, cables sent—but the atmosphere had changed. So had the stakes.

Moreno quickly broke from his predecessor, citing the need for economic pragmatism and geopolitical balance. In 2019, his government withdrew Assange’s asylum. The arrest followed within hours.

Relations between the two countries shifted gears. Talks resumed. New trade deals were signed. Military cooperation restarted. In 2020, Moreno met with then-President Donald Trump. The message was clear: Ecuador was back at the table.

Behind the scenes, the embassy was a facilitator of this reset—negotiating customs enforcement agreements, coordinating with U.S. agencies on counter-narcotics efforts, and expanding public diplomacy. Migration—especially the protection of Ecuadorian nationals in the U.S.—became a core focus.

Although the work of the embassy has continued to be a persistent forward force, the structure itself has not gone unchanged by time. In 2011, a minor earthquake sent one of its chimneys crashing onto parked cars. In 2017, a fire ripped through the upper floors, drawing more than 100 firefighters. The damage was significant, but not terminal. Restoration followed. The embassy reopened.

A 2002 Washington Post piece once described the building as “a well-worn smoking jacket, a little frayed at the cuffs but genteel nonetheless.”

Today, the Ecuadorian Embassy operates in a space somewhere between formality and function. It is not just a symbolic outpost, nor simply an administrative annex. It is where a small but consequential country does the work of staying relevant to a superpower: advancing trade, managing migration, defending sovereignty, and protecting its nationals abroad.

In that sense, the building is more than a relic of architectural ambition or a footnote to a diplomatic standoff. It is, still, a place where Ecuador negotiates its place in the world—with less spectacle, but with no less consequence.